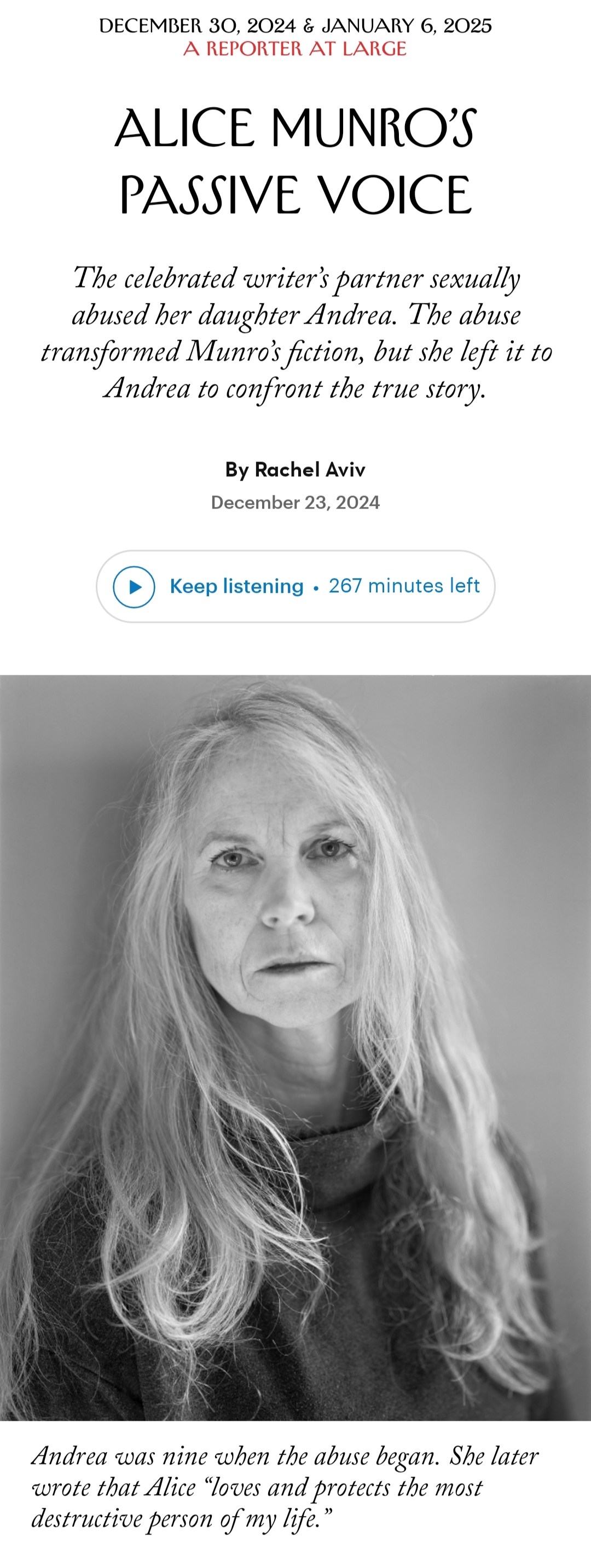

For years, Jenny had been trying to talk with her mother about something that had been put through the machine repeatedly: the sexual abuse of Alice’s youngest daughter, Andrea, by Gerry, and Alice’s refusal to see the harm that it had done. “She loves and protects the most destructive person of my life,” Andrea had written years earlier.

Alice used to shut down when Jenny brought up the subject, but after she got Alzheimer’s, Jenny said, “she didn’t feel invested in that person, Gerry, at all, or in the person she’d been with him. She started to lose that great terror over the truth.”

Jenny and her mother had lucid conversations about Andrea’s abuse, which Jenny sometimes recorded, but Alice would forget what had happened a few minutes later. In one conversation, in 2019, Alice exhaled loudly and said under her breath, “How awful.” She looked up at Jenny and said, “It was beastly of me not to get rid of him.”

“Did you sort of blame yourself and hate yourself and think Andrea would never love you again, too?” Jenny asked, hoping for more self-reflection.

“No, I don’t think it was that,” Alice said. “I don’t know why I didn’t.” She sat in a cushioned chair, wearing a zip-up sweater, a fleece blanket spread over her lap. Then she said in a louder voice, as if finally discovering something solid, “Well, he told me he’d kill himself, of course.” Gerry had said that he couldn’t live without her. “He was in a desperate situation.”

“And it’s an empty threat, isn’t it?” Jenny said. “What if Andrea had killed herself?”

“Yes, exactly,” Alice said, nodding.

“A lot of victims of child abuse do,” Jenny said.

Alice held her hand to her forehead. She seemed to be losing track of the emotional center of the conversation. “Does she think about it still?” she asked.

“This?” Jenny said. “It’s not something you get over.”

“Oh, God. Oh, God,” Alice said, in a high, pained voice, bowing her head and holding it in her hand.

评论: